28 Sep 2017 - Graham

previously: an article i co-wrote got published!

In the first month of this trip I often felt lonely, anxious and dissatisfied.

(I listened to this song a ton because this Cat Power covers record I found in an Oakland thrift store was one of only 3 good CDs I had in the car)

I think it took me about a month of travel to adjust and, thankfully, to find a happier way of being on the other side.

At first, being alone in the woods wasn’t the transcendent experience that Walt Whitman and John Muir set me up to expect. Maybe I should have known better. Before this trip, I liked to go for hikes. But my patience for the outdoors was limited. After a few hours outside, I would get bored and find myself eager to be inside with internet and air conditioning. So I began to think, especially in my first forays into the woods, that I simply wasn’t an outdoors person. In contrast, John Muir was regularly beaten by his father, a zealous preacher and farmer, for going wandering, and yet he persisted in spending as much time as possible in the woods in Scotland and later Wisconsin. He also seems to have thoroughly enjoyed fighting with other schoolboys, so he may just have been a pro-conflict type of boy.

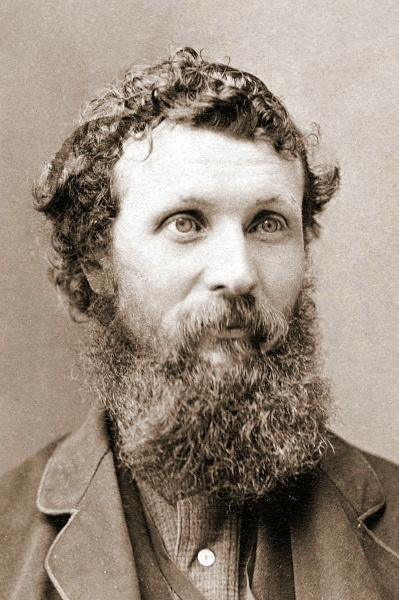

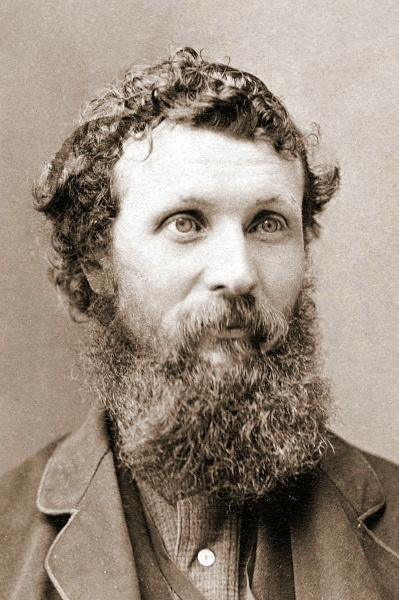

In either case, I’m clearly no Muir. (I mean, just look at that beard! Though we do seem to share some curly locks.) As a child I did not feel the same deep and immediate connection to nature. To be sure, I spent lots of time in our yard and around the neighborhood, but I never explored widely. And unlike Muir, I did so because of parental encouragement. I would never have persisted in spending time outside under the threat of beatings. Then again, Muir also didn’t have the thrilling adventures and multiple choice conversations of the Monkey Island computer game series waiting for him inside.

On my first backpacking trip in Kings Canyon National Park, which I’ve blogged about before, I found myself in one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world climbing a path along dramatic waterfalls under majestic peaks and yet I was not quite awed. It was great, I knew how beautiful it was. And at one point I did feel amazed, even tearing up at an unusually expansive meadow. But the feeling didn’t last. I didn’t feel a special connection to the plants, animals or landscape around me. I didn’t feel an ecstatic sense of oneness with the universe. Instead, I found myself trying to guess how many miles were left and then figure out how many miles per hour I was moving. I wondered about the internal lives of the other hikers. Like, what brought these other people out here? And I kept thinking about the same things I had been thinking about in civilization. The things Whitman calls “indoor complaints” in the first part of his “Song of the Open Road”

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road, Healthy, free, the world before me, The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose. Henceforth I ask not good-fortune, I myself am good-fortune, Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone no more, need nothing, Done with indoor complaints, libraries, querulous criticisms, Strong and content I travel the open road.

In contrast to Whitman’s promises of freedom and light-heartedness and self-sufficiency, that first night in the Kings Canyon wilderness was a real low point.

Without my phone to distract me, I felt a gnawing sense of dissatisfaction. I was bored. Bored in a way I haven’t been since maybe middle school summer vacations (after I’d used up my daily hour allotment for computer games). Bored, like then, in the midst of an experience and freedom I had been eagerly looking forward to for a long time. And so the dissatisfaction was also accompanied by a sense of guilt. How could I be bored on summer vacation! Especially on adult summer vacation next to a bubbling brook under the tallest trees in the world in the midst of the most beautiful mountains.

I was bored, in part, because I was avoiding purposeful work. On those long middle-school vacation days, I was often avoiding chores and summer reading. In the woods, the chores were much easier to do because the consequences of not making dinner or cleaning my dishes was more immediate and harsh (starvation, attracting bears, &c…). But in the woods I found myself again struggling with required reading. In this case, it was an entirely self-afflicted assignment. I had brought with me, on an e-reader than can hold a nearly infinite supply of books, only two books. Two important works of turn-of-the-last-century literature: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience. These were books that I hadn’t ever quite gotten around to reading. (Though, my good friend Ross had introduced Leaves of Grass to me by reading the inspiring Songs of the Open Road aloud in a park in Philadelphia more than a month before). Wouldn’t this be a perfect time to force myself to read them? The simple answer, and my answer at the time, was something like: “No, you dummy! Don’t take on two big challenges at once. Read the tough books when you’re somewhere comfortable, and bring easy books on your first ever solo backpacking trip.” But reflecting now, the double challenge was an important part of the experience.

For one, I now love both books dearly, and I probably wouldn’t have gotten so into them if I had been in a comfortable place with other options. In fact, in my tent that first night, I found that James explained why I was having so much trouble reading Whitman. James’ take on Whitman is an adoring criticism - he finds him to be on the level of the greatest saints and also a bit overly enthusiastic. Whitman’s relentless optimism let’s him see, and thus to begin to shape, a better world. But it also means his account of the world mostly leaves out the ordinary person’s experience of negative emotions.

Or, perhaps, if I’d read Whitman more carefully I could have found a more sympathetic voice. Just now, as I was looking for the Whitman quote above, I noticed that the next two paragraphs of the poem, while still enthusiastic, spoke also to the mixed emotions of travel and an inability to ever escape from worldly concerns into a realm of pure freedom:

The earth, that is sufficient, I do not want the constellations any nearer, I know they are very well where they are, I know they suffice for those who belong to them.

(Still here I carry my old delicious burdens, I carry them, men and women, I carry them with me wherever I go, I swear it is impossible for me to get rid of them, I am fill’d with them, and I will fill them in return.)

Contemporary fiction would have let me escape the toughness of the experience and it would have let avoid thinking the thoughts that being alone in the woods forced me to think through. Part of the work that I was avoiding was internal emotional work.

For example, I hadn’t deeply realized (or “groked”) how dependent I have become on the hundreds of tiny social affirmations (texts, likes, matches, etc…) that my cell phone usually provides each day. The disconnection was destabilizing. I discovered that my sense of self, of being a person other people like, is shockingly tied to the digital currencies of social media. Without those affirmations, I didn’t just feel alone, I felt unliked.

Being alone in the woods forced me to face my dissatisfaction head-on and thus to find that it was rooted in deeper anxieties. Anxieties like: (1) Am I having the optimal experience right now? (2) Do people actually like me? And (3) will something/one try to hurt me or steal from me?

Over time, I started to get more used to being without constant access to the sedative distraction of my phone. And more used to sleeping outside after long hikes. And to being alone. I may not have been an outdoors kid when I started this trip, but I surely am now. In the parks I visited in the second half of my trip, Lassen Volcanic, Zion, the Grand Canyon, Carlsbad Caverns, and Big Bend, I found myself considerably more comfortable and satisfied. Just like the Rolling Stones warned me, I found that I didn’t need lots of the things I thought I needed. I didn’t need the internet or my phone to feel loved; or coffee shops and restaurants to feed and caffeinate me; or a comfortable bed and locking doors for a safe night’s sleep; or toilets and laundry and air conditioning for physical comfort; &c… As a result, I gradually began to feel that deeper ecstatic connection with nature that Whitman and Muir proclaim.

My time on the road gave me room to think productively about those thoughts I had been avoiding. Thanks to a month of directly encountering deep fears, I was able to find productive solutions. Solutions like: (1) The best experiences are the experiences you pay the most attention to, so stop worrying about what else you could be doing or what you think you should be feeling. (2) Yes, lots people love you (thank you, family, dear blog readers and incredible hosts along the road). And (3) you can do basic things to make your world safer (bear canisters, zipped up tent, locked doors, advocacy for redistribution from the rich to the needy) but you can’t be perfectly safe and there’s less than no sense trying to be. These were all things I sorta knew, before like in an abstract way. But on this trip I really lived them.

next post: issue 1: join or die